- From the Bank

- Posts

- What I learned about winter bass from a redfish duck pond

What I learned about winter bass from a redfish duck pond

(the simple system I use to choose the right water when it is cold)

Hey, Keith here.

The biggest challenge in winter bass fishing doesn’t start with picking the right lure.

It starts with picking the right water to fish.

You can have the perfect jig or finesse rig tied on, but if you are standing in front of the coldest water in the area, you’ll be at a disadvantage all day.

Growing up in southeast Louisiana, I learned a simple rule from years of hunting redfish: Winter fish always slide toward the warmest water available.

I might have learned this in the saltwater marsh throwing Little Cleo’s for redfish, but it applies just as much to bass in lakes, rivers, and ponds.

Today, I break down my winter system for deciding to fish a big lake, a river, or a tiny pond and how that choice changes before and after a cold front.

BEST LINKS

What I looked at this week

Fishing for bass in the winter: 10 winter bass fishing tips (Anglers)

Hot pond bass strategies for this winter (Wired2Fish)

2025 winter bass fishing in ponds: Best lures and tactics (Pond Fishing for Bass)

Where do bass go in the heart of winter? (Tactical Bassin’)

Where to fish in the wintertime? Lake, river, or pond (Bass Resource)

Deals of the week

Bass Pro Shops marked down a Abu Garcia 4 STX Baitcast Reel from $89.99 to $46.97.

KastKing knocked $100 off its Mg-Ti Elite Magnesium Baitcasting Reel, regularly priced $399.97, now $299.99.

Academy reduced the price on Magellan Outdoors Men’s Rubber Camp Boots from $49.99 to $34.99.

DEEP DIVE

How a redfish duck pond taught me where to bass fish in winter

Being raised in southeast Louisiana, I grew up chasing redfish in the saltwater marsh. In winter, the entire game revolves around one thing: finding warm water.

Over and over again, I learned the same lesson. If I could locate the warmest pocket of water in the marsh, I caught fish. If I fished the coldest water, I struggled.

The shallow duck ponds scattered across the marsh were the perfect teachers.

Most of them are only 1–3 feet deep, and when a hard cold front pushed through and the temperatures dropped, those ponds turned into some of the coldest water in the whole system.

The redfish would slide out of them and fall back into the deeper canals where the water was more stable.

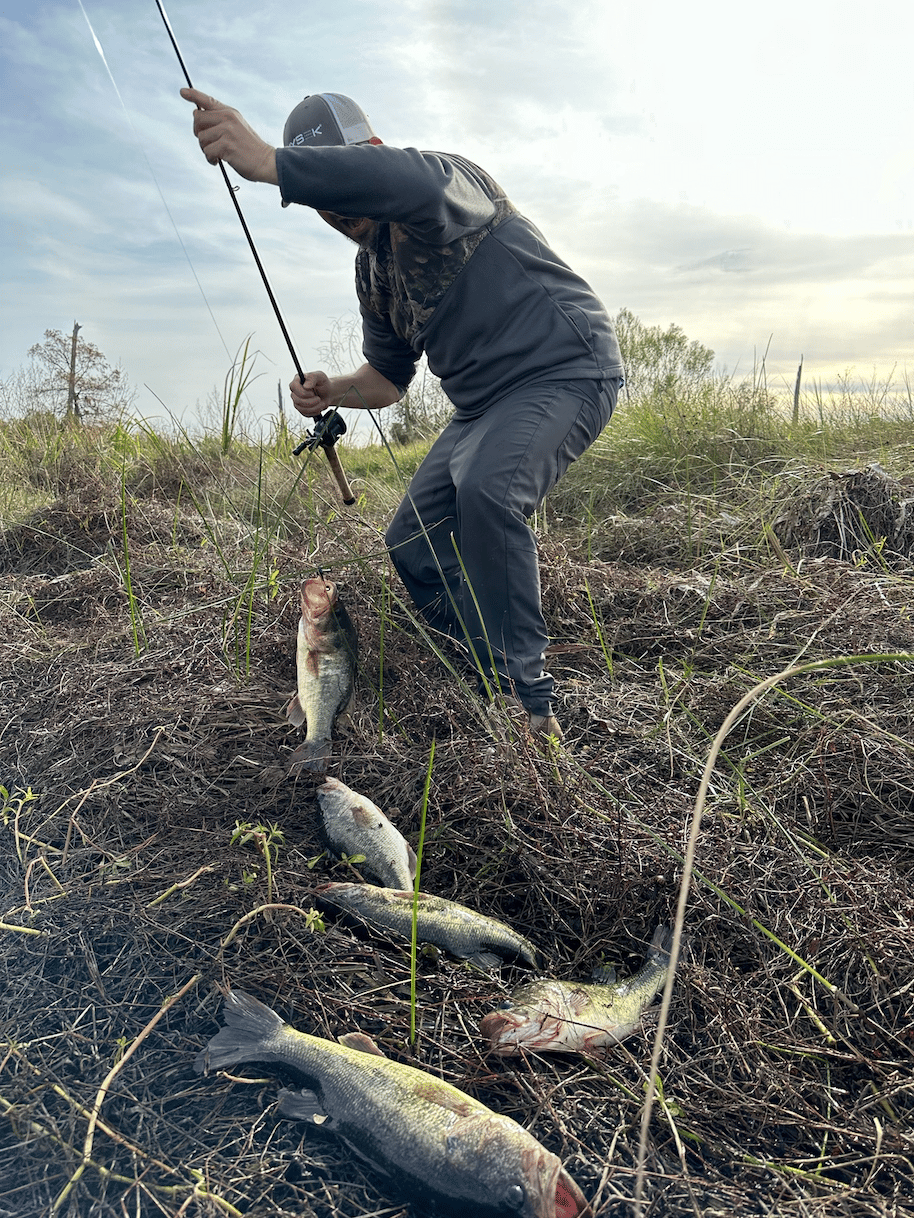

Here is a redfish I recently caught in a duck pond just south of Lake Borgne in the Biloxi Marsh.

But a few days after the front, when the sun came back out and the weather started to warm, everything changed.

Because those ponds were so shallow, they heated up faster than the deeper canals around them.

On a sunny, calm day, they would become the warmest water in the entire marsh. When that happened, the redfish moved right back in, and we crushed them with Gene Larew’s.

That pattern taught me something I have never forgotten.

In winter, the best fishing is almost always where the warmest water is, and which spot is warmest depends entirely on the timing after a front. It's a lesson I carried straight into my bass fishing.

One of my favorite places to fish in December is this shallow ditch that drains from the marsh on Bayou Cane in Southeast LA.

Why water choice matters so much in winter

Bass are cold blooded; their body temperature and activity level follow the water.

In colder water, their metabolism slows and they feed less often, but they are not shut down. They simply settle into zones where the temperature is a little more comfortable and the food is nearby.

In deeper lakes and ponds, winter often sets up a cold top layer with slightly warmer water sitting deeper in the water column. That deeper layer can sit around the upper 30s or low 40s and stay more stable than the surface, which swings with every cold wind that blows across it.

Shallow ponds are the opposite, especially when the sun shines on less frigid winter days. Because they are small and shallow, sunlight can reach more of the bottom and the whole pond can warm faster than a large, deep lake.

Current also affects water temperature. Running water tends to stay cooler than still water, especially in shallow streams and rivers. Faster, thinner water loses heat quickly and is constantly mixing, which makes it harder for a warm pocket to form.

Put simply:

On the coldest days, deep, still water usually offers the warmest refuge.

On sunny warming days, shallow still water warms the quickest.

Moving water is usually the last place to warm up.

My simple system for choosing winter water

Here is the basic system I use now when I am deciding between a river, a lake, or a pond in the middle of winter.

1. Look at the last few days of weather.

Ask yourself two questions:

Did a strong cold front just move through and drop air temps into the 30s and low 40s?

Or are we a few days past the front with sunshine and highs in the 50s or 60s?

That timing tells you where the warmest water is most likely to be.

2. On the coldest days, pick a big lake or deeper water.

When temperatures have just bottomed out, I stay away from small ponds. That shallow water cools quickly and there are no deep refuge holes for the bass.

Instead, I look for a larger lake with some true depth, where the bottom layers can stay a little warmer and more stable than the shallow edges.

Bass slide off into those deeper zones and hold around channels, drops, or steep banks where they have easy access to food without fighting the coldest water in the system.

I like to throw lures that I can whip out far, like a Zumverno, and cover a lot of water.

From the bank, I focus on places where I can reach deeper water with a cast. Points, bluffs, and shorelines that drop off quickly are all good options.

3. Avoid strong current when it is truly cold.

Winter water with a strong current is usually colder than still water nearby. So, when the air is in the 30s and low 40s, I put rivers at the bottom of the list unless they have slow, deep pools that act more like small lakes.

Sunshine and shallow water lead to these bass on a cold December day.

4. On warming days, move to small ponds.

A few days after a front, when the sun comes back out and highs reach the 50s or 60s, I flip the script. That's when I want to be on a small pond throwing something like a Bitsy Bug or a Baby Brush Hog.

Shallow ponds warm faster because sunlight can reach more of the bottom and there is less water volume to heat up.

On a calm, sunny afternoon, that little pond might be a few degrees warmer than the big lake down the road. It may not sound like much, but to a cold-blooded bass, two or three degrees can be the difference between lockjaw and feeding.

When I fish a pond on a warming trend, here's where I focus my attention:

Banks that get the most sun

Dark, muddy bottoms that soak up heat

Protected corners where the wind is not mixing the water as much

Just like those Louisiana duck ponds—first place to cool when the front hits, first place to warm when the sun returns.